By: BRITTNY MEJIA, LOS ANGELES TIMES – AUG. 16, 2020

The young Mexican Americans boarded boats and a seaplane that brought them to the shores of Santa Catalina Island.

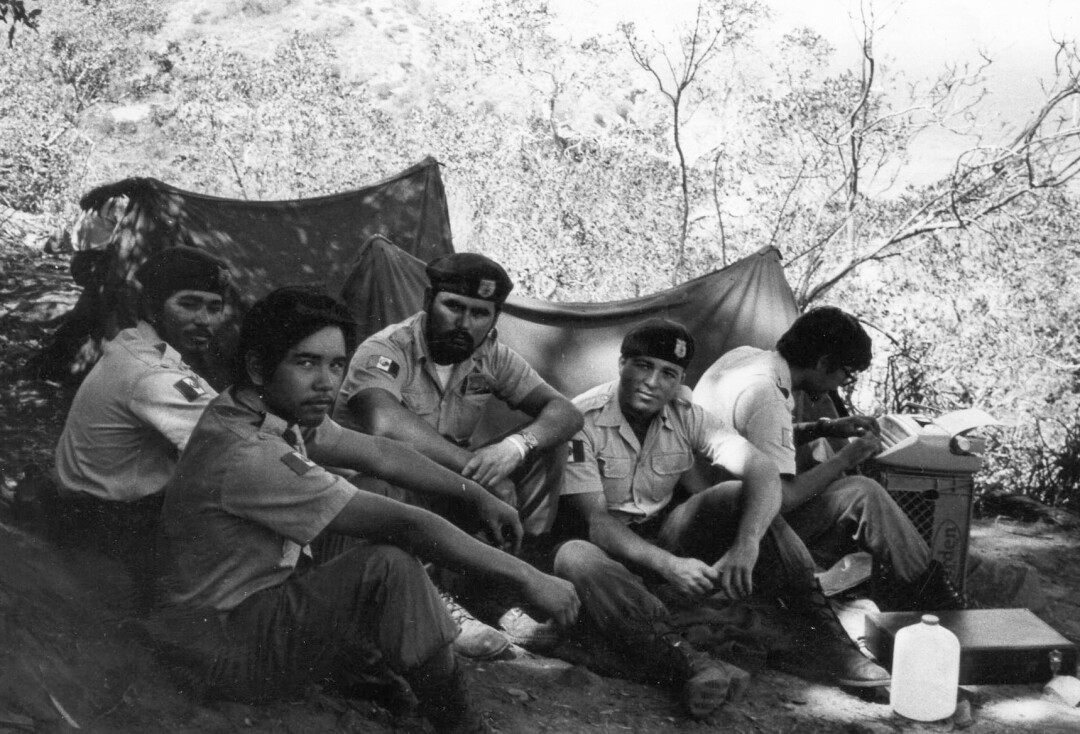

They wore conference badges that identified them as members of a Catholic youth group, but they had wrapped paramilitary-style uniforms in blankets. They placed them in duffel bags, alongside tents and a flag the size of a dining room table.

On land, they pretended to be tourists. They knew that they could be arrested for what they were about to do. Two of their men scouted the island terrain before settling on a small patch of land.

Within days of landfall, they trekked to a hill north of the Catalina Casino in the small town of Avalon. There, they changed into dark brown pants, khaki shirts and their signature brown berets, from which the group took their name.

They used rope to string up their flag between the trees facing the yacht-dotted harbor. The distinctive red, white and green with the snake-eating eagle of Mexico rippled in the breeze.

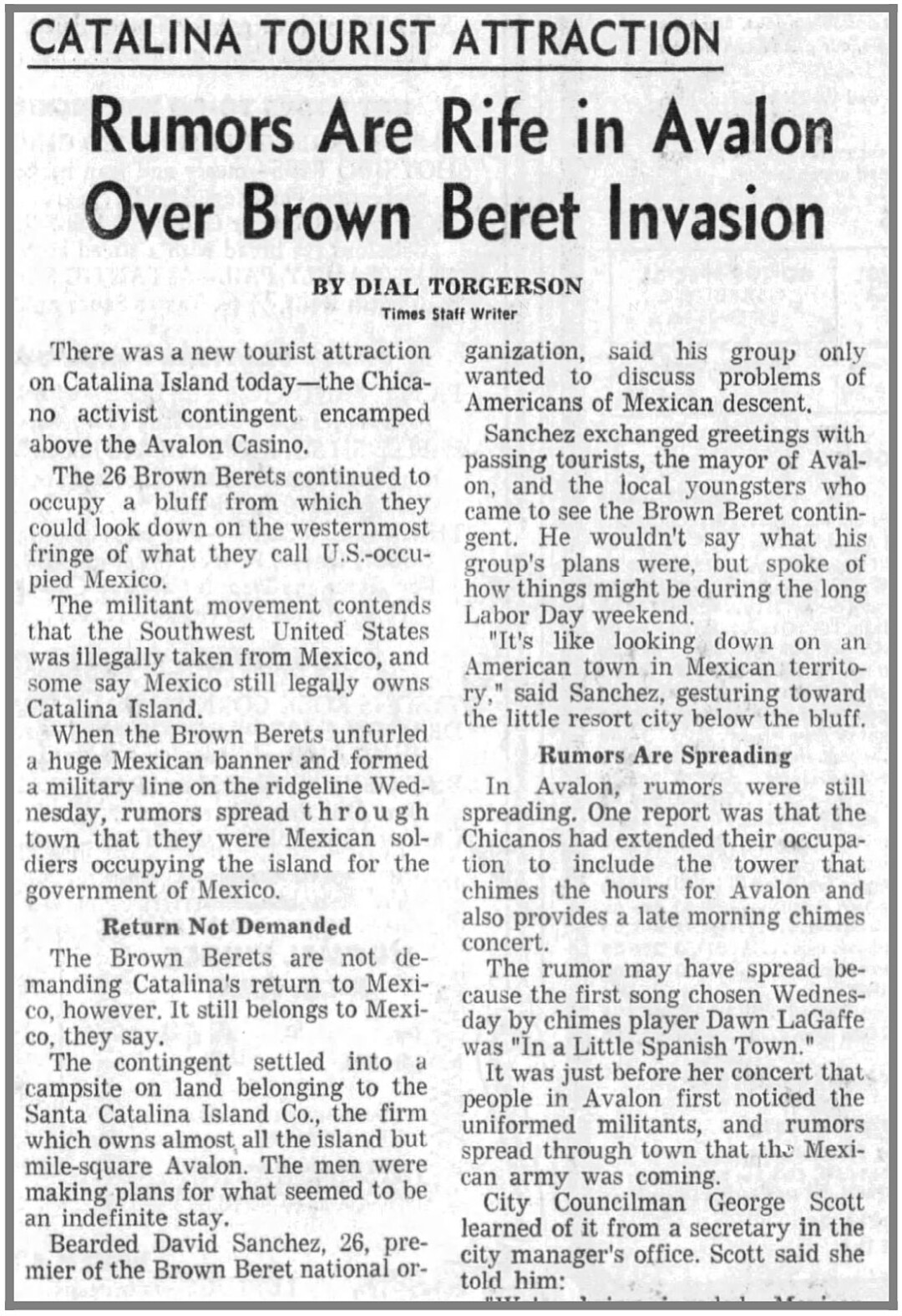

Shortly after 10:30 a.m., someone looked up and spotted the 26 Brown Berets in military formation on the ridgeline.

“We’re being invaded!” a secretary in the city manager’s office told a councilman. “Mexican soldiers are claiming the island!”

It was the summer of 1972 and the mission of the Brown Berets was to occupy this land — which they believed rightfully belonged to Mexico — as a symbol of the Chicano movement. In a scene that felt straight out of a Chicano Wes Anderson film, the 25 men and one woman traveled to a hillside above Catalina Chimes Tower and set up camp.

When sheriff’s deputies arrived at Campo Tecolote — Camp Owl — the Brown Berets’ founder and “prime minister,” David Sanchez, handed them a 16-page news release. In it, he argued that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had ceded California to the U.S. but did not cover islands offshore.

“By this plan, we wish to bring you the true plight of the Chicano, and the problems of people of Mexican descent living in the United States,” Sanchez wrote.

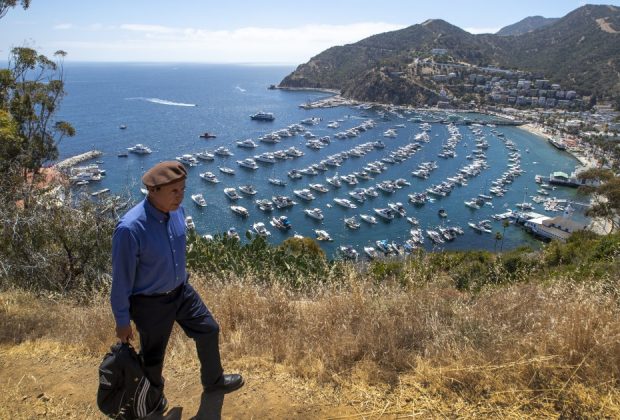

Nearly 48 years later, Sanchez stepped carefully off the Catalina Express boat. White flecked his eyebrows. His brown beret now covered thinning black hair and age spots.

Time had changed not only him but also the Brown Berets’ legacy on this island.

“Are you going to visit Burrito Point?” Ariella Markowitz, a reporter who grew up in Avalon, asked after Sanchez had disembarked.

“Where’s that?” Sanchez said.

“That’s what the locals call your spot,” she said, sheepishly.

Sanchez burst out laughing.

::

In the 1968 East Los Angeles Blowouts, at least 10,000 students from East L.A. high schools and beyond staged weeks of boycotts and protests of run-down campuses, a lack of college prep courses and teachers who were poorly trained, indifferent or racist.

The walkouts served as a catalyst for the Chicano civil rights movement.

The climax of the movement, some experts say, was the Chicano Moratorium demonstration Aug. 29, 1970, when about 20,000 people took to the streets of East L.A. to protest the Vietnam War. Journalist Ruben Salazar died in the chaos after the march, struck by a sheriff deputy’s tear gas projectile.

The Brown Berets’ adventure — or, depending on whom you ask, misadventure — came two years later.

“The Chicano movement was on a decline,” said Sanchez, who was part of the blowouts and the moratorium. “I felt that we had to do an event that would put the Chicano movement back on the map.”

So on Aug. 30, 1972, they set up camp, hoping to gain publicity for la causa.

Over the next few weeks, the Brown Berets marched through town, went grocery shopping and attended church with fellow townspeople — all in uniform. They circulated fliers to townspeople, signed by Sanchez, that ended with, “Peace on earth and welcome to MEXICO.”

For Joe Rey, the island felt a world away from the El Paso desert where he grew up. Some days, he visited the beach with his fellow soldados, who became like family. He had no sympathy for anxious locals.

“What’s going to happen to my family if they kick us out of the island?” a resident asked.

“Too bad,” Rey told him. He thought: “When they took over our land, they didn’t care about us. Why should we care about them?”

(Almost half a century later, Rey is no longer a fiery young leftist. In fact, the 72-year-old is a conservative Republican who freely admits that it was fun, but there’s no way he would support such an action now.)

The group received food from some of the 300 Mexican Americans who lived in Avalon. Among those helping was the family of Maria Lopez, who lived on Tremont Street, along with most of the town’s Latinos.

Her mom and tías made enchiladas, beans and tacos for the group. Her father delivered them to the Brown Berets.

“The Mexican people here, the Chicanos, welcomed them,” Lopez said. “But a lot of the gringos, they were afraid they were coming to take over.”

‘The Chicano movement was on a decline. I felt that we had to do an event that would put the Chicano movement back on the map.’

DAVID SANCHEZ, FOUNDER OF THE BROWN BERETS

American flags suddenly went up across town, including a large one unfurled on the hillside above the encampment, according to the local newspaper, the Catalina Islander. The next day, the flag was brought back with tears and cuts, which were blamed on the Brown Berets.

Late one Thursday night, on Sept. 21, residents held a “vigilante-type meeting” to “take care of” the group, according to Mayor Raymond Rydell’s report in the paper. A few men brought a chartered boat with the intention of putting the Brown Berets on it and sending them to the mainland.

Ultimately, a sheriff’s sergeant calmed the crowd and residents returned home. The next day, a judge — joined by sheriff’s deputies — walked into the encampment and told the Berets they were violating a town ordinance prohibiting camping in an area zoned for single-family dwellings. If they didn’t leave, he said, they would be arrested.

The group didn’t want to risk those younger than 18 being detained and sent to a youth detention center, Sanchez said. But he admitted that the order came as a relief, as the Chicano movement was declining on the mainland and the Brown Berets had been receiving fewer supplies and funds.

“In a way,” Sanchez said, “it was a blessing in disguise.”

So, after nearly a month, the occupation was over. That afternoon, the Brown Berets boarded the GT Avalon to take them to San Pedro. As they chanted “Chicano Power,” the local paper reported, those on shore sang “God Bless America.”

“Living in the same town with these soggy, chocolate soldiers for three weeks was not pleasant for anybody,” Rydell wrote after their departure.

“The few among us who assisted the Brown Berets by befriending them and bringing them food were actually fraternizing with misguided militants who are at war with American society, who wish to destroy it, and substitute for it a racist culture based on who your ancestors were, instead of what you are.”

By 10 a.m. the day of Sanchez’s visit, the streets of Avalon were crowded with foot traffic. The town has a population of about 4,000, but it boasts over a million annual visitors.

That morning, tourists navigated golf carts — the main mode of transportation — through the 2.8-square-mile town.

Although many of the visitors wore masks because of the pandemic, Sanchez was the only one wearing a brown beret. As he walked through town, he struggled to remember how to reach the spot where he once camped out for nearly a month with Chicanos from California, Arizona and Colorado.

At times he flipped to a 10-page chapter on the Catalina mission in his book “Expedition Through Aztlán.” His memory occasionally conflicted with what he wrote.

Instead of journeying under a beating sun, Sanchez decided it would be too difficult to hike to the former encampment. After all, he was no longer the 24-year-old who had laid claim to the island.

“Excuse me,” Sanchez asked a taxi driver. “How much do you charge just to take us up to Burrito Point?”

“It’s really called Campo Tecolote,” he told the driver, once inside the taxi. “I was the leader of the Brown Berets that came over here and took over the island many years ago, probably before you were here.”

“I wasn’t here,” the taxi driver said, “but I heard about it.”

Here on Santa Catalina Island, the so-called invasion of 1972 is mostly a footnote.

In the Catalina Island Museum, among the exhibits on the island’s history, there is no mention of the Brown Berets’ occupation decades ago. Doing an exhibition on the invasion has long been on the list, but the museum doesn’t have artifacts related to that time.

In the former camp, off Chimes Tower Road, there are no markers — only shards of bottles and discarded beer cans.

Many of the old-timers who were on the island then, including former Mayor Rydell, have long since died. Some who remain say the event was mostly forgotten about after the Brown Berets left.

“It was just a blip,” said 89-year-old Rudy Piltch, who has lived on the island for over 40 years. “A fascinating moment, but a brief one.”

Outside the island, it’s a part of Southern California history that is known by a fair amount of people, mostly Mexican Americans whose roots go back generations. But many other people, probably most, have no idea about the event.

“It’s not anywhere as well known as the Chicano Moratorium, or the blowouts in ’68,” said Mario T. Garcia, professor of Chicano studies and history at UC Santa Barbara. “It did get attention, but I don’t know that it was very lasting.”

There are no books written specifically on the invasion, he said, but it was significant because the Brown Berets were “trying to teach people about Chicano history.”

“I think a lot of the attention was focused on this idea of Brown Berets invading, or the idea that some of the people on the island felt that this was the Mexican army coming to take over Santa Catalina Island,” he said. “The history lesson that David and the others were trying to teach I think got somehow subverted in that.”

The dirt crunched under Sanchez’s feet as he walked down a familiar path that led off the main road. He smiled as he pointed out the spot, now covered in brush, where he’d pitched his tent. And the ridge where the Brown Berets would line up for inspection each morning at 8 a.m. Not much had changed, he said.

“I think they reserved it for us,” he said.

He grew somber as he recalled the day the Brown Berets left the island. He told everybody they would someday return to Catalina Island to occupy it. But when they got back to the mainland, he said, it seemed “like a lot of people were turning against us.” Now, he returns — at least every other year — only to visit.

Sanchez took a final look around: “It was a good spot. Until time ran out.”

Over lunch at Antonio’s Pizzeria, Piltch and Sanchez sat across from each other as they shared memories of 1972.

Piltch, who was in his 40s at the time, recalled waking up one morning to the sight of the Mexican flag. He described it as “a little bit of a shock to a lot of people.”

From what he recalled, Piltch said, “a lot of the local Hispanics at the time, I think they kind of felt offended.”

Mayor Rydell’s report in the local paper seemed to echo that sentiment. He wrote that islanders of Mexican descent had been “unfairly embarrassed” by the Brown Berets’ presence.

“These islanders are Americans, not Mexican-Americans,” Rydell wrote. “In this real democratic community of Avalon, there are no hyphenated Americans … just Americans. We all stand under the same flag. Don’t let these racist Brown Berets confuse you.”

Piltch asked Sanchez whether he had good memories of his time in Avalon. The only bad memory, Sanchez said, is when they were told to leave.

“I remember there was a boat that came in … they brought all of your group down, put you on the boat and sent you home,” Piltch said.

Sanchez laughed, before he responded:

“This is our home.”

By: BRITTNY MEJIA, LOS ANGELES TIMES – AUG. 16, 2020