By:

The fax machine beeped and screeched as it transmitted a two-page document to the FBI. I was a low-level reporter for the Los Angeles Times working out of a storefront news bureau on Exposition Boulevard in South L.A., chasing answers to questions that the newspaper should have asked decades earlier about the death of one of its own.

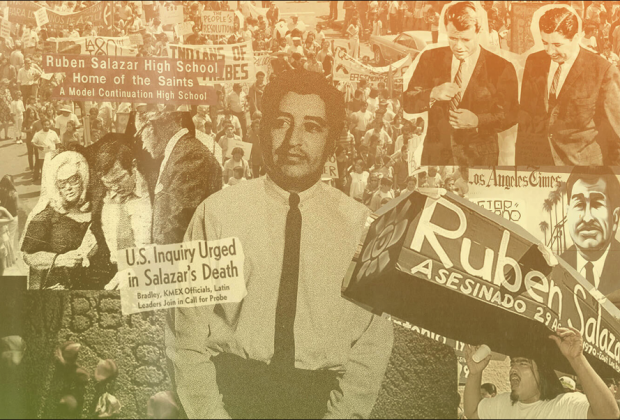

Without the knowledge of my editors and unsure of what I might be dredging up, I faxed a Freedom of Information Act request to the FBI, searching for clues to a momentous but neglected chapter in Los Angeles history: the slaying, by a sheriff’s deputy, of Los Angeles Times columnist and KMEX-TV news director Ruben Salazar.

That letter, which I sent to the FBI on June 14, 1994, launched me on a journey that has continued to this day. It led me to investigate and challenge the actions of law enforcement agencies in the months leading up to Salazar’s slaying, as well as to try to uncover new details surrounding his death amid a tumultuous anti-Vietnam War and civil rights protest in East Los Angeles on a hot, smoggy afternoon — now 50 years ago.

The more I dug into the past, the more I began to question the historical role of The Times in failing to deeply investigate the killing of a trailblazing journalist who opened the city’s eyes to the hopes and frustrations of its long-overlooked Mexican American community.

I also questioned my role as a Chicano journalist who was hired at a time — not unlike now — when the Los Angeles Times was under fire for the failure of its newsroom to mirror the ethnic and racial diversity of the communities it covered.

Salazar was a pioneer whose award-winning journalism opened the door for a generation of Latino reporters like me. I felt a responsibility to focus attention on a grave injustice. But most of all, I was hoping to break news that might shed light on a killing that remains a source of speculation and suspicion to this day.

Was Salazar’s slaying nothing more than a tragic accident at the hands of a deputy who was operating under “riot” conditions, as law enforcement authorities contend? Or was Salazar targeted, as some of his closest friends and activists believe, to silence his hard-hitting reporting of police actions in Los Angeles’ Mexican American neighborhoods?

Over the years, the story kept pulling me back as I tried to answer these questions, and eventually I came to my own conclusions about what happened that day on Aug. 29, 1970, when sheriff’s deputies swooped down on the Silver Dollar Bar & Cafe.

Early code switcher

In death, Salazar became a mythic symbol for a movement and the people he covered as a journalist. In reality, he was a complicated figure, a skilled code switcher who could easily navigate between white and Latino worlds.

Colleagues at the Santa Rosa Press Democrat, where Salazar was the Petaluma bureau chief in 1956, told me how he exposed secret government meetings and searched for restaurants that served menudo, the familiar Mexican stew of red chile pepper, tripe and hominy. After joining The Times, Salazar lived with his family in Orange County, the land of Richard Nixon and the right-wing John Birch Society.

Salazar became a foreign correspondent, one of the Los Angeles Times’ most prestigious assignments. He covered a U.S. military invasion of the Dominican Republic in 1965, reported on the war in Vietnam at a time of growing U.S. involvement, and became the newspaper’s Mexico City bureau chief.

Salazar in front of the Old Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Mexico City. He was the newspaper’s Mexico City bureau chief. (Los Angeles Times)

In January 1969, Salazar returned to Los Angeles to cover a Mexican American community that had transformed dramatically. The civil rights movement had swept across the barrios of the Southwest, where activists had begun calling themselves Chicanos. Emboldened by cultural pride, Chicano protesters were speaking out against generations of racism and discrimination, substandard educational opportunities, law enforcement abuse and the war in Vietnam, where Latinos were dying in large numbers.

A year after returning to Los Angeles, Salazar left The Times to become news director at Spanish-language KMEX-TV. But he agreed to write a weekly column for the newspaper focusing on the Mexican American community.

His columns were a radical departure from the straightforward news articles he had written as a reporter. In his first column, he offered an unapologetic explanation of why Chicanos resented being told by whites that speaking Spanish was a problem. “Chicanos will tell you that their culture predates that of the Pilgrims and that Spanish was spoken in America before English,” Salazar wrote. “So the ‘problem’ is not theirs but the Anglos’ who don’t speak Spanish.”

Salazar understood the power of television to reach large audiences in a growing Spanish-language community. Each weeknight, his hour-long “Noticiero 34” newscast attracted nearly 300,000 viewers, making it one of the most-watched local news shows. “The reason, undoubtedly, is a newly gained pride in the Spanish language by the nation’s second largest minority,” he wrote in one of his columns.

Death at the Silver Dollar

At KMEX, Salazar’s small news crew aggressively covered growing tensions between Chicano activists and the Los Angeles Police Department and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. Concerned about the reporting, police visited Salazar at the station and warned that he was damaging the reputation of the LAPD. “Besides, they said, this kind of information could be dangerous in the minds of barrio people,” Salazar wrote in a July 24, 1970, column.

On Saturday morning, Aug. 29, 1970, Salazar met KMEX cameraman Octavio Gomez and reporter Guillermo Restrepo near Belvedere Park in East Los Angeles, where crowds were gathering for the National Chicano Moratorium Against the Vietnam War.

National Chicano Moratorium marchers in East L.A. in 1970. (Los Angeles Times)

As the summer sun burned through a smoggy haze, at least 20,000 men, women and children marched nearly three miles to a rally at Laguna Park (later renamed Ruben F. Salazar Park). They chanted “Chicano Power!” and hoisted banners — “Houston,” “Denver,” “Albuquerque” — proclaiming the far-flung places from where they had traveled for the historic gathering.

It was the high point of a burgeoning movement and at the time was one of the largest civil rights marches in Los Angeles history. But the rally exploded into violence after sheriff’s deputies responded to reports of thefts at a liquor store near Laguna Park. Deputies decided to clear the peaceful gathering, firing tear gas canisters into the multitudes sprawled on the grass as helmet-clad, baton-wielding officers charged forward.

Protesters battled with police and dark clouds of smoke rose into the air as buildings were set on fire along Whittier Boulevard. Salazar and Restrepo worked their way east, stopping at the Silver Dollar Cafe to use the restroom, then decided to grab a quick beer.

Meanwhile, sheriff’s deputies responded to a report of two armed men inside the bar, a report that later proved false. Deputies fired several tear gas projectiles through the curtained doorway, including a 10-inch torpedo-shaped missile designed to rip through plywood in barricade situations. It struck the 42-year-old Salazar in the head, killing him as he sat at the bar next to Restrepo, who crawled out through a back door while choking smoke filled the small space.

Interior of the Silver Dollar Bar & Cafe in East Los Angeles, where Times columnist Ruben Salazar was found dead on Aug. 29, 1970. (Frank Q. Brown / Los Angeles Times)

Finding the rift

On a hot summer day in El Paso, I sat in a conference room packed with reporters at the 1995 National Assn. of Hispanic Journalists convention. Four panelists were lauding the groundbreaking work of Salazar, who was raised in the Texas border city and had cut his teeth as a cub reporter at the El Paso Herald-Post.

A year had passed since I sent my letter to the FBI. My request for records was being processed and it was unclear how long that would take. I had sent similar requests to the LAPD and Sheriff’s Department but was told they didn’t have the records I was seeking.

The Los Angeles Times wanted to publish something substantial for the 25th anniversary of Salazar’s slaying, which was just two months away, and it was my job to make that happen. But as the panel in El Paso was winding down, I didn’t have a story. Until a respected journalist spoke up.

Charlie Ericksen, easily recognizable with his glasses and grizzled beard, stood from his chair and looked at the panelists. “I’m one of those people who still firmly believe that Ruben was a victim of a political assassination,” he flatly said.

A founder of the Washington, D.C.-based Hispanic Link news service, Ericksen, who started his career as a copy boy at the Los Angeles Mirror, had helped launch the careers of many Latino reporters. Without elaborating, he told the gathering that Salazar believed police were after him. I scribbled into my reporter’s notebook. I had a lead to chase.

As I later found out, Ericksen and Salazar were close friends. Ericksen and two other friends — a Catholic priest and the director of the L.A. office of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights — had met the newsman at an Olvera Street restaurant three days before he was killed. In separate interviews, the three men described Salazar as shaken, worried that he was being followed by police. He feared police would do something to discredit his reporting, they recalled.

Their recollections were compelling. Salazar was a veteran journalist who had covered combat overseas. Early in his career, he had pretended to be drunk and was arrested by El Paso police. The ruse enabled him to expose wrongdoing in the city’s notorious jail. Clearly, he was not a man who was easily scared.

Restrepo, the former KMEX reporter, said he and Salazar were investigating allegations that Los Angeles police and sheriff’s deputies had planted evidence on some suspects and beaten others. The two journalists had been tipped off: Authorities knew about their investigation.

“We were in hot water,” Restrepo told me.

I landed another promising lead. A year earlier, the LAPD had responded to my records request, saying the counterterrorism division had no records of Salazar. That was true, but through my reporting I learned that an intelligence file on Salazar had been compiled for former Chief Ed Davis. It was buried in city archives.

I went to the cavernous warehouse where tens of thousands of boxes of historical city records are stored. The LAPD file revealed a bitter rift between Salazar and Davis. The chief had accused Salazar of reporting a “total lie” regarding comments he made in a meeting with Latino journalists. Davis demanded that Salazar apologize — which the journalist refused to do, saying his report was accurate.

“I’m one of those people who still firmly believe that Ruben was a victim of a political assassination.”

Ruben Salazar during his tenure as news director of the Los Angeles Spanish-language TV station, KMEX. (PBS)

The file, which contained transcripts of KMEX news reports and photocopies of Times articles, disclosed a disturbing detail: A “reliable confidential informant” at the newspaper had passed information about Salazar to the LAPD. Salazar, police were told, was a “slanted, left-wing-oriented reporter.” I never confirmed the name of that informant but knew through my reporting that Salazar didn’t trust some of his colleagues.

I contacted Davis, who criticized Salazar, saying he lacked objectivity and was “not some kind of diplomat or peacemaker.” The former chief said in the 1995 interview that he wasn’t aware of police shadowing the newsman, but he acknowledged it might have occurred. “If he was surveilled, it might have been done unauthorized by some lower level officer,” said Davis, who died in 2006.

On Aug. 26, 1995, the Los Angeles Times published my 3,200-word article on Salazar. It was a solid story that featured details not previously reported by the newspaper. Still, I had found no conclusive evidence that law enforcement authorities were tailing Salazar or knew he was in the tavern when the deadly projectile was fired.

I hoped that the FBI documents, which I was still waiting for, would provide new clues.

Opening the files

Tourists strolled past colorful piñatas, intricately woven shawls and other handicrafts as I sat with a colleague, then-Times columnist Héctor Tobar, at La Luz del Dia Restaurant on Olvera Street in late June 2010.

It was the same restaurant where a shaken Salazar had met his three friends, telling them he suspected police were after him. We were there to meet a powerful Los Angeles County official who might be able to help us uncover new information about Salazar’s slaying.

After 15 years, my search for records had largely resulted in one disappointment after another. Documents from the U.S. Department of Justice were of little help. A request to the CIA prompted a cryptic response: Agency officials could neither confirm nor deny the existence of any records on Salazar, saying such information was classified.

But the biggest setback came from the FBI. More than five years after I had requested records, I finally received more than 200 pages of documents. Some portions were redacted, for what officials said were national security reasons. The records failed to yield any new information on the circumstances of Salazar’s slaying.

I had hit the end of the reporting road — until a tip pulled me back.

In early 2010, I learned from a source that the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department had more than half a dozen boxes filled with files related to Salazar and the Chicano Moratorium. The existence of these records had not been disclosed to me when I filed my original request with the department in 1994.

I sent a new California Public Records Act request to the Sheriff’s Department seeking to review the files. On March 10, then-Sheriff Lee Baca denied my request.

Hoping to avoid a battle for the records, I met the department’s media liaison on March 18 and told him it was in everyone’s interest to open the secret files. He indicated that Baca was reconsidering his denial of my request and was “inclined to release” the records.

I had yet to receive a response from Baca about the files when Tobar and I had lunch at the Olvera Street restaurant with a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors.

The five supervisors on the board wielded considerable influence over Baca because they controlled his department’s budget. During an off-the-record conversation, Tobar and I played the game of asking questions, yet we made it clear we believed the files should be unsealed and that any assistance from the supervisors would be in the public interest.

In death, he’s been made more radical than in life.

In early July, Tobar wrote a column about Salazar and called on the Sheriff’s Department to open the files, saying it could help heal the wounds of a 40-year-old case.

Baca denied my request again on Aug. 9. At that point, I knew that the best strategy was to keep this story in the news. Over the next three weeks I produced five articles and a news video. The newspaper published a strong editorial saying it was time to end decades of obfuscation.

The day after my first article was published, the Board of Supervisors ordered the county counsel to prepare a report about whether the files should be made public. Around the same time, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund was working with a documentary filmmaker to press the Sheriff’s Department to release the files.

On Aug. 19 I met a source at a downtown street corner, where I was handed a large envelope with a copy of the confidential report from the county counsel to the Board of Supervisors. I raced back to the newsroom to write a story. The county’s own attorneys had concluded that some of the records should be made public under state law.

Lopez looks at a painting of former Los Angeles Times reporter Ruben Salazar and a copy of his last story, published on August 28, 1970, the day before he died, on display inside Ruben Salazar Memorial Hall at Cal State LA. (Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Baca had turned over the files to the Office of Independent Review, a civilian watchdog agency created to monitor the department. Over the next six months, the office reviewed the records and took the unprecedented step of investigating a 40-year-old case. The office announced it would prepare a public report of its findings.

A few days before the report was made public, I was given a copy by my source and wrote a front-page story published Feb. 19, 2011. The report said deputies made a series of tactical errors that led to Salazar’s killing but found no evidence that he was targeted or had been under surveillance. The report acknowledged that its findings were limited regarding whether Salazar was targeted because that line of investigation was not pursued by homicide detectives assigned to the case.

In early March 2011, the Sheriff’s Department finally opened the eight boxes of files for reporters to review. I pored over the voluminous records. They contained interesting revelations, including details of law enforcement surveillance of community groups involved in the Chicano Moratorium.

But the files contained no new information answering the questions that I had first set out to investigate more than 15 years earlier.

Role of The Times

I never wanted to be pigeonholed into writing stories focusing solely on Latino issues. But this was a story about a fellow Los Angeles Times journalist who was killed. It transcended simplistic boundaries.

When I first came up with the idea of sending a Freedom of Information Act request to the FBI, I was sure that someone at the newspaper had already done so. No one had.

I spent years asking questions and reporting facts that the Los Angeles Times should have asked and uncovered in the weeks and months following Salazar’s slaying. By the time I got involved, the trail was cold. People’s memories had faded and key records could have been lost or destroyed.

After Salazar’s slaying, The Times largely covered breaking events about the case — including a 16-day coroner’s inquest, a fact-finding proceeding that focused more on the unrest and less on the circumstances of Salazar’s death. It also produced an investigative piece that called into question the use of the deadly projectile. But for the death of one of its own, the newspaper should have launched a crusade to find additional new evidence and hold people and agencies accountable.

Ruben Salazar, top center, with his fellow Los Angeles Times reporters. (Los Angeles Times)

Had the newspaper looked hard enough, it could have discovered key details, including that federal prosecutors had convened a grand jury to investigate Salazar’s slaying. I learned of the grand jury in 1995 from Jerris Leonard, former U.S. assistant attorney general for civil rights. The Catholic priest who met with Salazar at Olvera Street told me he testified before the panel. The federal investigation quietly closed in March 1971 without any charges being filed against the deputy who fired the deadly projectile, according to U.S. Justice Department records I obtained.

Bill Thomas directed local coverage for the Los Angeles Times when Salazar was killed and later became editor of the newspaper. In a 1995 interview, he insisted that his reporters were thorough in their coverage. “I don’t know how you could have been any more aggressive than we were,” Thomas told me. He died in 2014.

A former high-ranking Times editor offered a different narrative.

Frank del Olmo was well respected and the first Latino named to the masthead of the Los Angeles Times. Hired in 1970, he was mentored by Salazar and became a columnist and associate editor. He died in 2004, after suffering an apparent heart attack in the newsroom.

“They just wanted to be done with it as quickly as possible.”

frank del olmo, former times editor

Del Olmo was on the Salazar panel at the 1995 El Paso journalism conference, where he acknowledged that he and other Los Angeles Times reporters “never really were allowed” to fully investigate the newsman’s slaying. He said the killing created an emotionally difficult situation and that Thomas was not comfortable with launching an exhaustive reporting effort, according to a transcript of the panel discussion.

“The comfort level wasn’t there — to allow his reporters to go out and find out what happened, and as a result, we let that ball slip right between our legs,” Del Olmo said. “So, we bear some responsibility.”

Salazar’s death, Del Olmo told the journalists in the room, was “a painful issue” for his newsroom colleagues.

“They just wanted to be done with it as quickly as possible.”

Circumstantial evidence

In recent months, I’ve seen history repeating itself.

I was hired by the Los Angeles Times in 1992, as part of a grand experiment called “City Times,” a section created for neighborhoods historically neglected by the newspaper — the “hole in the doughnut,” as editors called the area.

At the time, the newspaper was criticized for not doing enough to hire journalists of color. It had largely failed to recognize social and economic forces fueling civil rebellion that exploded in April 1992, after a jury acquitted four LAPD officers who had brutally beaten Rodney G. King, an unarmed Black man. City Times was a zoned news section launched in September 1992 in response to the criticism. It was shuttered in August 1995.

Today, the Los Angeles Times is under fire yet again for failing to hire and promote more reporters of color. The issue spilled into the public realm during the coverage of the Black Lives Matter protests in Los Angeles and across the country following the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

As I watched news of the protests, I saw police fire tear gas projectiles at reporters doing their jobs and thought of Salazar. But there are important differences between then and now.

For one, our ability to fully comprehend what happened to Salazar during a monumental chapter in L.A. history is limited without real-time video. There were black-and-white photos of deputies wielding weapons at the Silver Dollar, and there were conflicting eyewitness accounts. But there was no real-time video footage.

Imagine the King beating without George Holliday’s camcorder footage of LAPD officers swinging their batons. Imagine Floyd’s graphic killing without Darnella Frazier’s cellphone footage capturing a pivotal moment in the history of race relations and police violence in the United States.

In part because of the technological limitations of the early 1970s, we’ve been left with pieces of circumstantial evidence that allow us to draw our own conclusions about the tragic slaying of Ruben Salazar.

My conclusion? When sheriff’s deputies descended on the Silver Dollar 50 years ago, they didn’t think about whether their actions would result in injury or death. They didn’t care who was inside that bar.

This incident would not have played out the same way in a white neighborhood. But this was East Los Angeles, a Mexican American barrio. Sheriff’s deputies were never held accountable for their actions.

In the end, Salazar died from the very type of law enforcement abuse he was trying to expose.

Lopez was part of the team of Los Angeles Times reporters that won the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for public service.

By: