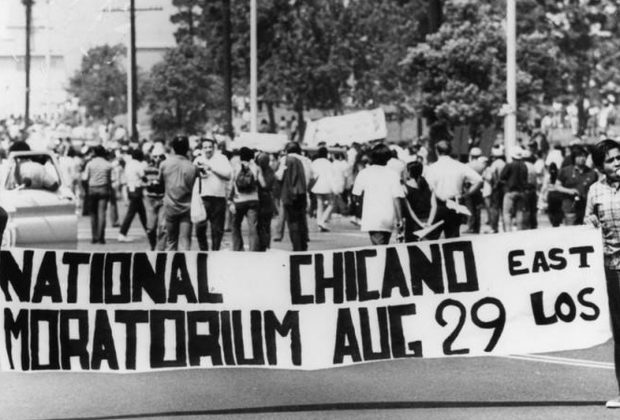

By Monica Lopez | KCRW | AUG. 29, 2022 | Photo courtesy of LA Public Library

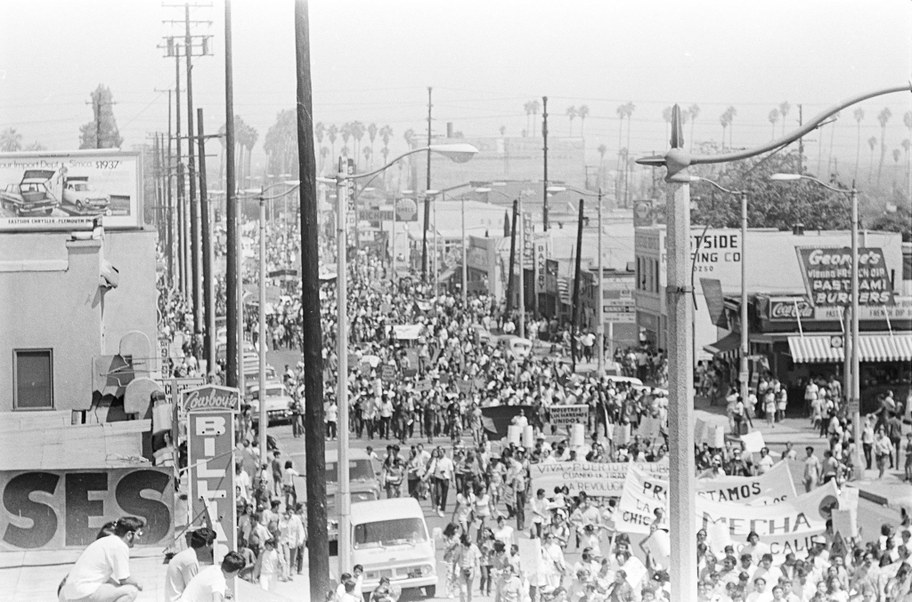

Fifty years ago, 30,000 people marched to Laguna Park in East LA. They were mostly Chicanos. The three-mile march was called the Chicano Moratorium. “Moratorium” because they wanted to stop the disproportionate number of Latinos dying on the frontlines of the Vietnam War.

People also came from Texas, New Mexico, and New York to protest substandard education, racism, and police violence.

“It was a wondrous event,” said Rosalio Muñoz,spokesperson and chair of the National Chicano Moratorium Committee. “It was like a moving fiesta down the main commercial center of East Los Angeles.”

The rally at the park was almost picnic-like with small children and abuelitas in attendance.

Then the mood turned.

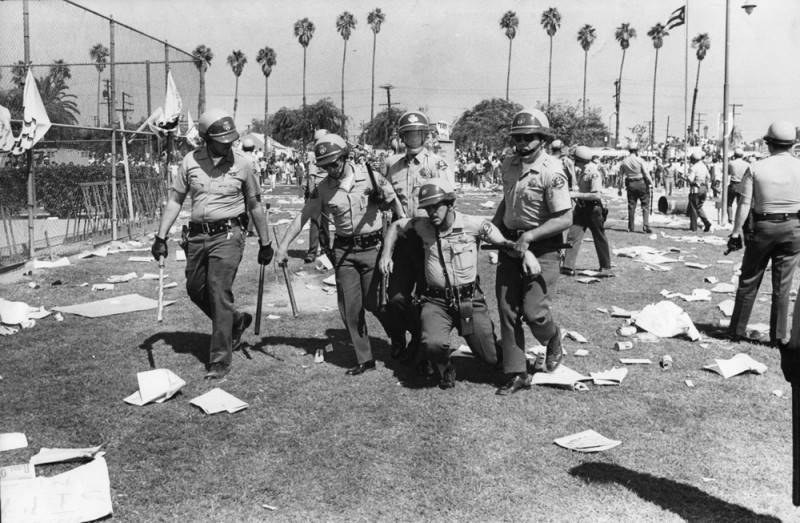

Former Brown Beret Gloria Arellanes went onstage to get a better vantage point. “All I could see at the back of the park was like a wave. People coming in and then moving out and then coming back again. And then, all hell broke loose,” said Arellanes.

What started as a peaceful demonstration ended violently. Riot-clad police attacked the crowd, and the crowd pushed back. When it was all over, 400 people were arrested, and four were dead. One of those killed was Los Angeles Times reporter and KMEX news director Rubén Salazar.

Jesús Treviño was an associate producer at television station KCET in Los Angeles. He and his sound recordist Henry Rangel spent the afternoon covering the marchers in the sun and then headed back to their car.

“Frankly, it was getting to be a little boring,” Treviño recalled.

Twenty minutes later, they were loading their equipment into the car near the entrance to a sheriff’s substation. Suddenly, the two men were overcome by sirens and cars emerging from the parking lot.

“Something like 35 different cars whizzed by,” said Treviño. “And in each of these sheriff’s patrol cars, there were four or five or even six officers jammed in there with full riot gear.”

Chicano Moratorium March, August 29, 1970 in East Los Angeles. Photo courtesy of Joe Razo from the publication “La Raza.”

News media found out later that one of the owners of the Green Mill liquor store called the police over a stolen six-pack of beer.

“I did the math,” said Treviño. “It was evident to me that they must have been waiting there for hours perhaps. And I think when the call came in about the Green Mill liquor store, that was the pretext they were waiting for.”

According to UCLA history professor Juan Gómez-Quiñones, some 500 police officers and sheriff’s deputies joined the melee that day.

In the foreground, helmeted police armed with clubs escort a collapsing officer as, in the background, other police confronts a wall of demonstrators during the National Chicano Moratorium in Laguna Park (renamed Salazar Park) on August 29, 1970. Paper, aluminum cans and handmade signs litter the grass. A line of tall palm trees in the distance marks the edge of the park. Photo courtesy of LA Public Library/Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection

Journalist Rubén Salazar and camera operator Guillermo Restrepo trailed after police who were chasing people east down Whittier Blvd. They eventually stopped at the Silver Dollar Bar and Café.

That was where Los Angeles County deputy sheriff Tom Wilson said he fired the tear gas canister that struck Salazar in the head.

Rubén Salazar was both the news director at Spanish language TV station KMEX and a columnist for the Los Angeles Times.

“Silencing his voice was a devastating move toward interracial, interethnic understanding,” said Félix Gutiérrez, professor emeritus at USC Annenberg School of Journalism. “And it showed that if you speak up too much, you might end up paying a price.”

The county set up a coroner’s inquest with clergy and community activists who could lend credibility to the investigation into Salazar’s death. One of those people was Irene Tovar, who currently sits on the City of LA’s Human Relations Commission.

“I guess to placate us, they created the inquest,” said Tovar. “We would go there every day, and they would be interviewing the sheriffs and the LAPD, and our role was to sit there and observe.”

“So they went through a showcase coroner’s inquest … and District Attorney Evelle J. Younger decided not to file any charges,” said Gutiérrez.

The LA County Sheriff’s Department historian declined to comment for this story on Rubén Salazar’s death or the investigation that followed.

Tongva elder Gloria Arellanes said the deaths of Lyn Ward, Angel Gilbert Díaz, Gustav Montag, and Rubén Salazar overshadowed the issues behind the moratorium.

Chicano Moratorium Committee conducts a march and rally commemorating the ninth anniversary of Chicano anti-Vietnam War demonstrations in Atlantic Park. Hernando Perez (right foreground) gets inspired as he watches the demonstrators. Photograph dated August 29, 1979. Photo by Ken Papaleo, courtesy of LA Public Library/Los Angeles Herald Examiner Photo Collection.

LA in 1970 was a very different place. At the time, most Mexican American political power came not from elected officials but from activism, like the East LA student walkouts of 1968.

“The farmworkers were organizing farmworkers. The leaders of walkouts for a better education — they were fighting for better education,” Rosalio Muñoz recalled “The ones fighting gerrymandering and to register voters, they were doing that. But we needed people that would focus on organizing against the war and nationally.”

The Chicano Moratorium march and rally propelled some who were there to create works of art, others to continue political activism, and many Mexican American journalists to follow the path cut by Rubén Salazar.

One small piece of his legacy stands today in what used to be Laguna Park, now called Rubén Salazar Park. On a wall by a parking lot in the park, the norteño band Los Tigres del Norte commissioned a mural by local artist Paul Botello. It shows themes of Chicano advancement and resistance and includes an image of Rubén Salazar himself.

A newly wedded couple march in the National Chicano Moratorium, which took place in East Los Angeles, August 29, 1970. Photo by Sal Castro, courtesy of LA Public Library/Security Pacific National Bank Photo Collection.